Stabil vækst men højt niveau af gæld. Strukturreformer er fortsat langsomme.

Political situation

Head of state: President Pranab Mukherjee (since July 2012)

Head of government: Prime Minister Narendra Modi (since May 2014)

Form of government: Centre-right coalition government of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Population: 1.29 billion

Landslide victory of the BJP in the 2014 general elections

In the April/May 2014 general elections the opposition BJP gained a landslide victory by winning an absolute majority in parliament (282 of the 543 seats in the Lower House); the first time since 1984 that any party has won a majority. The former coalition government of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) suffered a major defeat, with the Congress Party gaining only 44 seats (206 seats after the 2009 general elections). Before the elections, the UPA government struggled with widespread public dissatisfaction due to high inflation, slowing growth and several massive corruption scandals.

In contrast, the BJP front runner Narendra Modi had built a strong reputation as a competent administrator and economic reformer during his time as chief minister of the state of Gujarat. Modi and the BJP were also favoured by international financial markets due to their pro-business and reform-minded stance. However, despite the landslide election victory, the government still lacks a majority in the Upper House, which hampers the passing of major structural reforms in parliament.

Economic situation

Robust growth outlook in 2015 and 2016

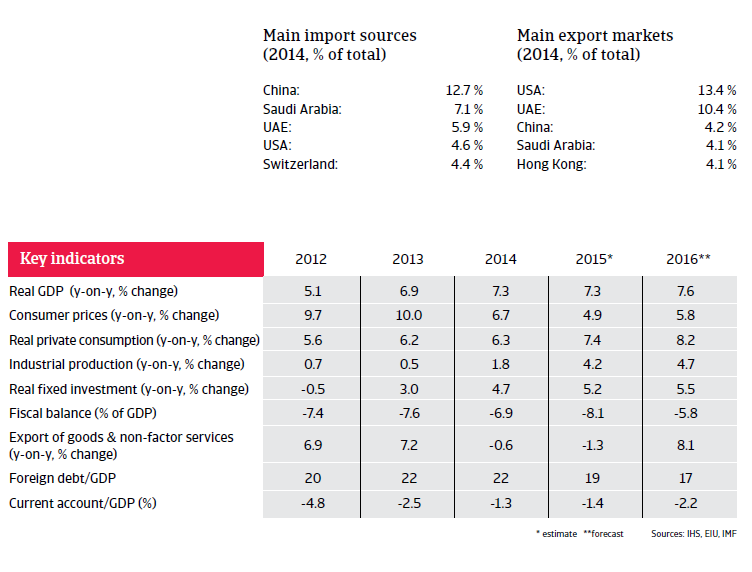

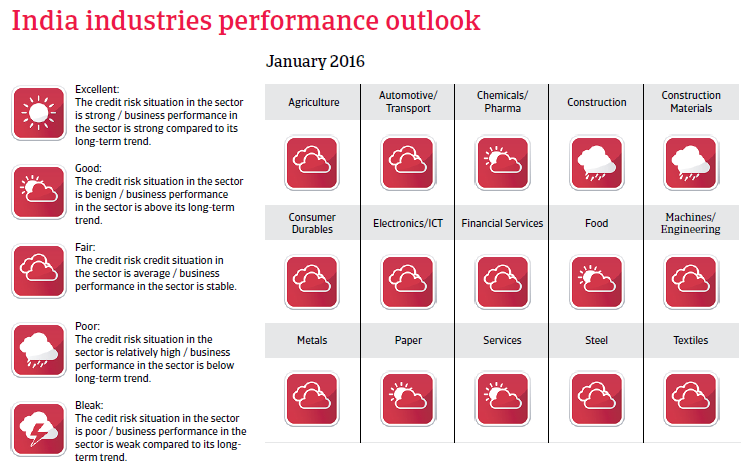

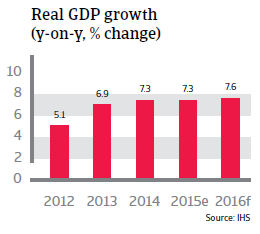

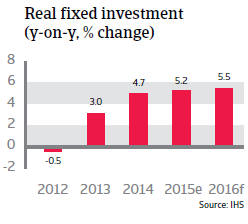

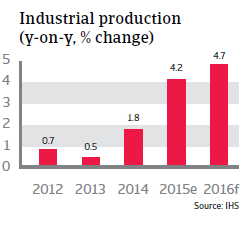

India´s economic outlook is the most promising in Asia in 2015 and 2016, with GDP forecast to increase 7.3% and 7.6% respectively. The economy benefits from a stable government, low oil prices (India is a large net oil importer), and high portfolio and direct investment. Domestic demand is increasing on the back of robust private consumption (up 7.4% in 2015) and increasing industrial production and investment. That said, the economic slowdown across some major emerging markets like China weighs on India´s growth as well - namely through lower demand for Indian exports. However, exports account for just 25% of GDP, which makes the relatively closed Indian economy less susceptible to decreasing external demand.

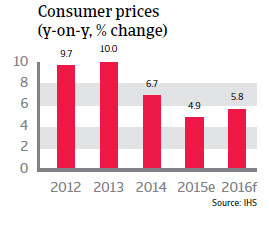

Inflation decreased below 5.0% in 2015

Inflation has decreased substantially since 2013 (from 10% in 2013 to less than 5.0% in 2015), due to lower oil prices and a prudent monetary policy by the Reserve Bank of India, which has adopted lower consumer prices as the major target since the end of 2013. In recent years, stubbornly high inflation of more than 9.0% and high interest rates deterred both consumer demand and investment. High consumer prices are a serious concern in India, undermining the purchasing power of the many poorer households.

External solvency is strong

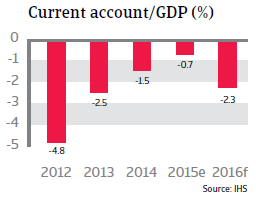

India´s country and sovereign risk remain low. Foreign debt amounted to only 22% of GDP in 2014 and is expected to decrease below 20% of GDP in 2015 and 2016 due to the robust economic growth. The liquidity situation is comfortable with more than eight months of import cover, while the current account deficits are expected to remain modest in 2015 and 2016. India has an excellent payment record, with no missed payments since 1970, providing it good access to capital markets. This generates substantial short-term capital and portfolio inflows.

In 2013 India, like some other emerging markets, became susceptible to the reaction of international investors to the anticipated ‘tapering’ by the US Federal Reserve (i.e. a reduction of its quantitative easing programme). A reversal of foreign capital flows resulted in a sharp depreciation of the Indian rupee and a deterioration in share prices.

However, in 2014 India won back the confidence of the international financial markets, and the depreciation of the rupee has eased since then.

Some major downside risks to higher growth remain

While India´s economy currently shows some major strong points, some downside risks to economic growth remain: the threat of government divestment in the face of a high fiscal deficit, the failure to increase business investment due to an overleveraged financial sector, and obstacles against reform efforts necessary to tackle the persisting structural problems.

High public debt and deficits remain an issue

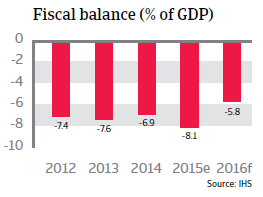

Public finances remain a weakness at both central government and state levels. Both general government debt and the general government fiscal deficit remained large in 2015, at 65% of GDP and 8+.1% of GDP respectively. The main reasons are the low tax base and still high expenditure on subsidies for fuel, food and fertilizer. However, these deficits can be widely financed by domestic borrowing, which mitigates the negative effects. The downside to domestic borrowing is a crowding out of private sector debtors.

Troubles in the financial sector and high corporate debt levels

The Indian corporate sector suffers from an overhang of debt: the average debt/equity ratio of Indian non-financial companies is more than 85%. The dollarization in domestic credit provision has increased significantly since 2013, while Indian businesses with large external debt levels are especially vulnerable to changes in capital flows, rising interest rates, and exchange rate volatility.

It comes as no surprise that the Indian banking sector is suffering from a high amount of bad debt. A major issue in this respect is the lack of a decent bankruptcy law in India, which impedes the successful recovery or restructuring of corporate debt and assets, and leaves non-performing loans (NPL) in the bank´s account books longer. According to the World Bank, it takes more than four years to wind up an ailing company in India, and the average recovery of debts amounts to just 25%. It is estimated that non-performing or restructured loans account for nearly 15% of the assets of India´s public sector banks (public sector banks account for about 70% of total bank loans). The concern remains that banks will not be able or willing to fund increased business investment in the future, and this would hamper higher economic growth rates. At least the government has launched a bankruptcy reform bill in November 2015, however it remains to be seen if it will be passed by the parliament soon.

Pace of structural reforms still too slow

India has many structural deficiencies: underdevelopment of the agricultural sector, poor infrastructure, inflexible labour laws, excessive bureaucracy, rigid land laws, and a shortage of skilled labour due to the poor education of most of the population. All these factors are barriers to foreign investment and higher growth.

Power supply, roads and railways, and the poor education system need to be urgently addressed, with more public/private investment partnerships needed for infrastructure projects. Even though former governments have repeatedly said they will increase incentives for private investors, so far private sector participation has focused mainly on the telecom sector, with investment in sanitation, power generation, roads and railways much lower than expected. Consequently, there is a continuing problem of power and water shortages in all of India’s major cities.

With the BJP adopting a more free-market and business-friendly stance, expectations for the new Modi administration have been high and, given the BJP majority in the Lower House, the chances of passing reforms are better than ever. However, the BJP still lacks a majority in the Upper House, meaning that it needs the support of opposition parties to pass major reforms. At the same time, Modi and the BJP have to take into account public sentiment and the power of labour unions.

So far, the Modi administration has imposed only incremental reforms. It has shied away from major cuts of fuel, food and fertilizer subsidies, which together account for a third of India’s huge fiscal deficit, but would be a highly sensitive - and unpopular – issue. In August 2015 crucial parts of a pro-industry land reform bill were withdrawn after meeting fierce resistance from opposition parties in parliament, and in September 2015 nearly 150 million workers, backed by 10 major unions, went on strike against plans to overhaul India´s rigid labour laws.

At the heart of the reform efforts is a national goods-and-services tax (GST), which would boost GDP substantially by removing barriers to trade between India’s many states and create a single market. Prime Minister Modi plans to launch the GST in April 2016, however, it remains to be seen if this deadline can be kept after the parliamentary opposition raised many obstacles. In any case, a compromise between government and opposition is needed.